Week 2: Asylum agreements with El Salvador & Honduras

Immigration news, in context.

This is the second edition of BORDER/LINES, a weekly newsletter by Felipe De La Hoz and Gaby Del Valle designed to get you up to speed on the big developments in immigration policy. Reach out with feedback, suggestions, tips, and ideas at BorderLines.News@protonmail.ch.

The Big Picture

Safe Third Country Agreements

The News: The United States signed asylum-related agreements with the governments of El Salvador and Honduras. As part of these agreements, both of the Central American countries are expected to begin receiving and processing some asylum-seekers who had arrived at the U.S.-Mexico border.

What’s happening?

While the signed agreements between the U.S. and the two Central American nations have been described as “deals,” they’re more of an understanding to work out a deal later. The agreement with El Salvador — signed by Acting Homeland Security Secretary Kevin McAleenan and Salvadoran Minister of Foreign Relations Alexandra Hill Tinoco — is all of six pages long. The key phrase comes in part 1 of Article 7: “The Parties shall develop standard operating procedures to assist with the implementation of this Agreement,” followed by a laundry list of procedures that need to be written and agreed on. The parties have pledged practically nothing beyond putting a deal in place, at some indeterminate future point.

In terms of the provisions, they’re pretty simple: Generally, the other country will allow the United States to send asylum-seekers to its own territory, as long as they’re not unaccompanied minors or citizens of that country. (For example, the U.S. can’t send Salvadorans to apply for asylum in El Salvador, the country they’re fleeing.)

There, the country commits to evaluating the asylum claims through its own administrative system. If someone's asylum application is denied, they can return to the U.S. to have their claim reviewed there. The text doesn’t mention, and the law technically doesn’t require, the asylum-seeker to have actually passed through the other country on their way to the U.S. first. If these agreements are implemented, this could mean the U.S. will try to send asylum-seekers to countries they never passed through.

How did we get here?

The Trump administration has been trying to get Mexico to sign a so-called “safe third country” agreement for months, but the Mexican government won’t budge. Mexican foreign minister Marcelo Ebrard has repeatedly said such an agreement is unnecessary, because Mexico has already taken measures to limit migrants’ ability to get to the U.S., including deploying troops to the U.S.-Mexico border.

A safe third country agreement with Mexico would be a huge boon for the Trump administration, because it would require every migrant who crosses through Mexico on their way to the U.S. — which is to say virtually every single asylum-seeker — to apply for relief there first. Those who didn’t would be returned to Mexico without being allowed to file a U.S. asylum claim.

The Trump administration did manage to secure an agreement with Guatemala in late July. (The U.S. has a longstanding agreement with Canada in place, which we’ll discuss further down; unlike the recent agreements, it has a full framework and is active). The Salvadoran and Honduran agreements mean the U.S. has secured these understandings, at least on paper, with all three countries in the so-called Northern Triangle.

Assuming they actually go into effect and the final language has them apply only to people who crossed through the “safe third” country’s territory, these agreements will all but guarantee that asylum-seekers from nations other than Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras will be prevented from filing for protections in the U.S. This would include a growing number of African and Asian migrants, often referred to as “extracontinental migrants.”

If they do not ultimately require territorial crossing, then virtually no asylum-seeker would have a clear path to filing an asylum claim in the United States. Eleanor Acer, senior director of refugee protection at the nonprofit organization Human Rights First, told The Intercept that the El Salvador agreement is so potentially sweeping that it could be used to “send an asylum-seeker who never transited El Salvador to El Salvador.”

At the very least, these agreements won’t allow immigration officials to send migrants back to the country they’re fleeing, because doing so would violate the principle of non-refoulement.

Immigration advocates have accused the Trump administration of using these agreements to deny asylum protections to vulnerable people, and that very well may be the administration’s intent. But safe third country agreements aren’t new.

For example, Canada and the U.S. have a safe third country agreement. Unlike the recent Central American agreements, the Canada-U.S. treaty only applies to people crossing at ports of entry, i.e., people who present themselves to customs officers to claim asylum, and only takes effect if a migrant is physically present in one of the two countries before entering the other.

The goal of the agreement is to prevent “venue shopping,” since the agreement presupposes that both countries are equally capable of protecting migrants from persecution. (Let’s say I’m an asylum-seeker and I set foot in the U.S. first, but then I decide I want to apply for protections in Canada instead because I prefer their healthcare system. That’s venue shopping.)

The European Union (and a few non-member states) have a similar agreement called the Dublin Regulation, which went into effect in 2013. (It’s based on the 1990 Dublin Convention, which first went into effect in 1997.) Like the American agreements, it requires migrants to apply for protections in the first country they reach.

According to a report by the Migration Policy Institute, though, the Dublin Regulation has had some unintended consequences. Instead of preventing venue shopping, it has incentivized asylum-seekers to avoid being detected until they reached their final destination, which has in turn increased demand for smugglers.

What’s next?

A similar agreement with Guatemala, signed in late July, is essentially at the same state of operational readiness as the two agreements signed this week. All of them allow either party to unilaterally pull out. Guatemalan President-elect Alejandro Giammettei — a staunch critic of the agreement during the campaign — takes office in mid-January, so who knows if it will ever go into full effect.

Much of the coverage has focused on the relative safety of Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, which provably cannot guarantee migrants’ safety. However, the law doesn’t actually require these countries to be generally “safe.”

Under the U.S. Code, asylum-seekers can be returned to a country with which the U.S. has an agreement if “the alien’s life or freedom would not be threatened on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion, and where the alien would have access to a full and fair procedure for determining a claim to asylum or equivalent temporary protection.” Whether or not a particular migrant will be safe is legally irrelevant; what matters is whether they will be specifically targeted for one of these reasons, and that there’s a system in place to evaluate their claims.

Even with this much more limited rubric, it’s questionable whether Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras qualify. Their asylum-processing systems are pretty limited; Salvadoran newspaper El Faro reported this week that the nation currently has a single asylum officer working to adjudicate claims. The other two aren’t on much better footing, and while the agreements stipulate that the U.S. will “strengthen [each country’s] institutional capabilities,” it’s not clear how they plan on getting the three systems to a point where they can deal with potentially thousands of applications.

Given that a good number of the Central American asylum-seekers showing up at the U.S. border are fleeing transnational gangs based in Central America, it’s dubious that they would be safe from the subject of their asylum claim if merely sent to a neighboring country. There is even evidence that asylum-seekers are, for practical purposes, often a targeted group in and of itself, beyond whatever their claim is based on.

For the time being, the existence of the “asylum ban” renders the point of when and whether the agreements go into effect sort of moot, except for one demographic: Any asylum-seekers who did not pass through another country on their way to the United States. In practical terms, this would be almost exclusively Mexican nationals, who cannot be returned to Mexico without a full adjudication and denial of their asylum claims, but could potentially be sent to one of the three other designated “safe” countries.

Under the Radar

DHS head touts end of “catch and release” | NPR

At a speech at the Council on Foreign Relations on Monday, acting DHS secretary Kevin McAleenan said immigration authorities will no longer release migrant families into the U.S. According to McAleenan, doing so will end the so-called practice of “catch and release,” the Trump administration’s term for releasing migrants into the interior while their immigration cases play out.

Instead, families will be asked whether they fear being returned to their home country. Those that say yes will be enrolled in the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), a misleadingly named policy requiring some Spanish-speaking asylum-seekers to wait out their cases in Mexico. Those that say no will be transferred to ICE detention and put in deportation proceedings.

At least that’s what we can assume based on McAleenan’s comments and a subsequent statement issued by DHS. But there are still a few unanswered questions: What will DHS do if a migrant says they don’t fear being returned to their home country but later files an asylum petition? (Migrants are allowed to apply for asylum within one year of arriving in the U.S.)

And what about Mexican asylum-seekers? They legally can’t be put on the MPP docket — though some have been — because doing so would violate the principle of non-refoulement. Put simply, governments can’t return asylum-seekers to the countries they’re fleeing without first determining whether they have a valid claim, and returning Mexican asylum-seekers to Mexico would do just that.

New York sues to stop ICE courthouse arrests | THE CITY

Brooklyn District Attorney Eric Gonzalez and New York Attorney General Letitia James filed a joint lawsuit against ICE in the federal Southern District of New York, alleging that the immigration enforcement agency’s practice of conducting arrests around state courthouses is illegal. Specifically, the prosecutors claim that the detentions violate the Administrative Procedure Act and the U.S. Constitution by interfering with state judicial proceedings and, in doing so, infringing on state sovereignty; being “arbitrary and capricious” in having failed to consider this harm; and go against long-established legal privileges restricting civil arrests in and near courthouses.

Immigration arrests in state and local courts has been a flashpoint in many localities, becoming a rare point of near-total agreement by actors in the criminal justice system, with defense attorneys, judges, and prosecutors all having expressed opposition. ICE claims that such arrests are the safest and most practical in ‘sanctuary’ jurisdictions that won’t help them detain immigrants or hold them in jails for ICE to arrive. Local officials, however, argue that it discourages victims from seeking recourse and prevents the criminal justice system from following its course. Often, people are arrested while going to court to face pending charges, which are much harder to resolve once they’re in ICE detention.

In April, the New York Office of Court administration issued new rules that prohibited ICE from arresting people in state courts without a warrant signed by a judge, with ICE agents very rarely have. In response, ICE mostly moved their arrests to just outside the courthouses. The lawsuit seeks to block this practice as well. It’s not the first case of its kind: two DAs in Massachusetts filed a similar lawsuit in April, and got a federal judge to issue an injunction stopping ICE from making court arrests in the state. Other prosecutors around the country may follow suit.

Next destination

Next year’s refugee cap will be an all-time low

The Trump administration will set next fiscal year’s refugee cap to just 18,000 people, a 40% reduction from this year’s historically low cap of 30,000. It’s a pretty unilateral decision: Congress created the refugee program through legislation, but gave president basically full authority to set the cap each year. Congress does have to be consulted about the annual ceiling, but that’s mostly a formality.

The proposal also included a breakdown of how many slots would be reserved for specific groups:

5,000 for people fleeing religious persecution

4,000 for Iraqis

1,500 for people from Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador

7,500 for all others

Almost at the same time as the State Department announced the cap, the president signed a bizarre Executive Order stipulating that refugees will only be resettled in jurisdictions where both state and local governments have “consented” to receive them. It directs the Secretary of Health and Human Services — the department manages refugee resettlement — to develop a process to determine this consent. Prior to this order, state and local governments had no mechanism to block refugee resettlements in their territory. This may be challenged in court, as refugee status allows individuals to resettle in the United States, not in any one particular jurisdiction.

It’s worth noting that the State Department suggested asylum-seekers are to blame for this year’s low refugee ceiling. “The United States anticipates receiving more than 368,000 new refugees and asylum claims in FY 2020,” the Department said in a statement. “Of them, 18,000 would be refugees we propose to resettle under the new refugee ceiling; we also anticipate processing more than 350,000 individuals in new asylum cases.”

But asylum cases are decided by immigration courts, and most asylum-seekers aren’t ultimately allowed to stay in the U.S. Meanwhile, refugee applications are vetted by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. And unlike asylum-seekers, refugees apply for relief from outside the U.S.

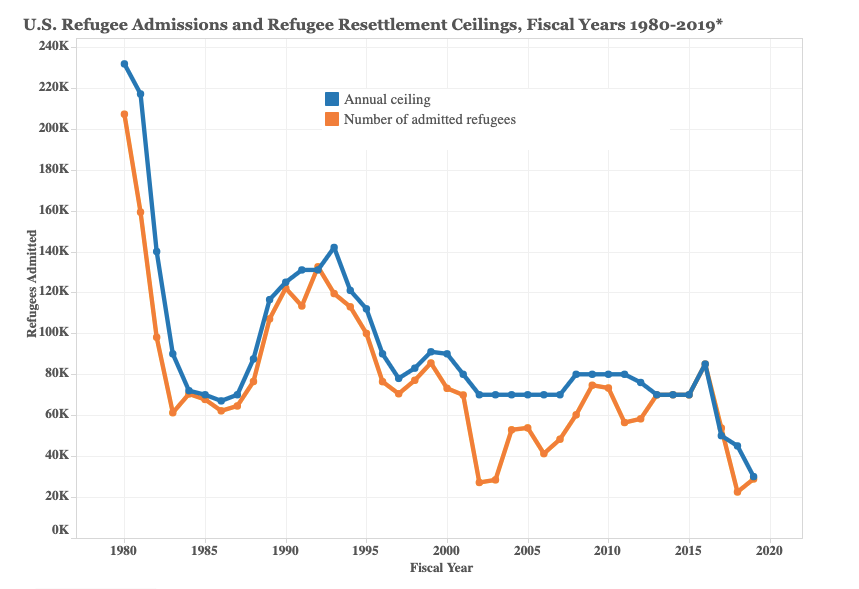

- Source: Migration Policy Institute (FY 2019 data are partial-year data, covering October 1, 2018 - September 11, 2019)

Refugee admissions have seriously declined over the past 40 years, and Trump isn’t the first president to drastically reduce the refugee admissions ceiling. That said, the number of refugees allowed to enter the country each year has steadily declined under Trump, and his administration has taken extra steps that have made refugee resettlement more difficult. The 18,000 number is also a cap, not a requirement, and the administration could resettle fewer if it chose to.

Resettlement agencies have warned that further cuts to the admission ceiling would have serious effects that will outlast Trump’s presidency; one agency was forced to shut down one of its regional offices earlier this year because of a lack of resources.

Judicial or legislative action on public charge?

Federal courts in the District of Columbia, the Southern District of New York, and the Northern District of California are considering legal challenges against the so-called public charge rule.

The new policy — which, in broad strokes, dramatically expands existing standards for government dependency when evaluating most visa and residency applications — is set to go into effect on October 15, but each of the lawsuits seeks an injunction preventing that from happening. District courts have lately shown themselves quite amenable to issuing nationwide injunctions against federal policies (so much so that Attorney General William Barr wrote an op-ed decrying them), so there’s a decent chance of this happening.

An injunction would prevent the rule from going into effect and would ostensibly protect immigration benefits applicants who would otherwise be subject to it. But it would also no doubt add to the mass confusion that has characterized the policy’s rollout and already led to many immigrants dropping their benefits. A Senate bill, S.2482, would also block the administration from implementing the rule, but it’s unlikely to go anywhere between now and mid-October.

Is the Fairness for High-Skilled Immigrants Act dead?

The bill (S.386/H.R.1044) would primarily eliminate the per-country caps on employment-based green cards per year, and raise the per-country cap to 15 percent of family-based green cards. Under the current system, one country can only receive up to seven percent of each of the available 140,000 employment visas (9,800 total for one country) and 480,000 family visas (33,600). This holds whether the country is China or Montenegro (some family-based visas are exempt). If the number of citizens of a country applying for residency exceeds the total allotment, they’re stuck waiting in a backlog, which has gotten so severe that some estimates point to the wait nearing a century for some categories.

The bill is a rare spot of bipartisanship in Congressional immigration policy, having been co-introduced by Sen. Mike Lee (R-UT) and Sen. Kamala Harris (D-CA). Despite this, it has been hugely controversial outside of Congress, mainly because of concerns that getting rid of per-country employment visa caps without significantly expanding the number of available green cards would allow nations with large employment-based residency backlogs — specifically, India and to a lesser extent China — to completely dominate the system. Essentially, such a move could reverse the current situation, such that nationals from any country but India and China would face years-long waits.

As a result, there has been fierce activism on both sides of the issue, which culminated this week in Sen. Lee attempting twice to bring the legislation to the Senate floor and being blocked each time. This may mean that the bill is totally dead, or it may mean that it will be rejiggered until it can pass.