Week 11: Challenges to administration effort to require local consent for refugee admissions

Immigration news, in context.

This is the eleventh edition of BORDER/LINES, a weekly newsletter by Felipe De La Hoz and Gaby Del Valle designed to get you up to speed on the big developments in immigration policy. Reach out with feedback, suggestions, tips, and ideas at BorderLines.News@protonmail.ch.

Many thanks to those of you who filled out our reader survey from last week. For those who haven’t gotten around to it, it’s not too late! Starting this week, we’re making some tweaks based on your feedback.

This week’s edition:

In The Big Picture, we explain the legal battle over a recent Trump executive order requiring states and localities to agree to refugee resettlement in their areas

For the first time, the executive branch is giving state and local governments the ability to essentially veto refugee resettlement in jurisdictions

Rather than requiring these jurisdictions to opt out of the refugee resettlement program, the order requires them to opt in

Three of the nine agencies that resettle refugees in the U.S. sued the administration last week, arguing that the executive order not only violates the Refugee Act of 1980 but also has discriminatory intent

In Under the Radar, we examine the ways two divisions of Immigration and Customs Enforcement have prepared for more arrests of immigrants already living and working in the U.S.

Per the Wall Street Journal, ICE’s Homeland Security Investigations division is increasing its focus on workplace investigations

And Quartz reports that in 2017, ICE bought a year’s worth of access to North Carolina DMV records for just $26.50

In Next Destination, we speculate what will come of the Trump administration’s decision to consider designating Mexican cartels as international terrorism organizations, as well as the outcome of the ongoing court case over the Trump administration’s asylum ban.

The Big Picture

The News: President Trump issued an executive order in late September requiring states and localities to affirmatively consent to refugees being resettled in their jurisdiction. Three of the nine national refugee resettlement agencies are now suing the administration over the change.

What’s happening?

Since the Refugee Act of 1980 (more on that below), the executive branch has held the power to determine the number of refugees to be resettled in the U.S. per year, the breakdown of types of refugee to be admitted, and, to an extent, where those refugees are resettled. The numerical limit and type allocations are pretty straightforward: each fiscal year, the president, after “appropriate consultation” with Congress, sets a ceiling on how many refugees can be admitted to the United States as “justified by humanitarian concerns or otherwise in the national interest (8 USC 1157(a)(2)), and sets allocations for “refugees of special humanitarian concern” ((a)(3)).

The Trump administration has set the maximum number of refugees for the 2020 fiscal year at 18,000 — the lowest in the program’s history. Those 18,000 slots will be divided among certain groups:

4,000 slots will be set aside for Iraqi nationals who aided U.S. forces in the country

5,000 for people fleeing religious persecution

1,500 for refugees from Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador

7,500 for everyone else.

The location of resettlement is a little more complicated. The first thing to understand is that, while the terms “asylum seeker” and “refugee” are often used interchangeably, the asylum and refugee programs are actually separate. They have the same requirements for fleeing persecution, but while asylum seekers have to start the process after arriving in the U.S. and have their cases decided by federal immigration courts, refugees go through the entire process outside the U.S., and then arrive with that status.

Potential refugees cannot directly apply on their own; they must be referred to the program, usually by the U.N., and typically undergo years of interviews and health and security checks before being allowed to travel to the U.S. This is why a numerical cap is possible, and why resettlement location comes into play. The refugees arrive already bound for a new home somewhere in the country, with the help of the government and one of nine national resettlement agencies, known collectively as the Voluntary Agencies or VOLAGs, which have specific agreements with the government to provide particular services, either directly or through affiliates.

For refugees, the path to the U.S. runs through several federal departments, as summarized in the following chart:

(Source: Department of Health and Human Services)

Trump’s late September executive order specifically targets this second step, in which refugees who are already approved are re-established in the U.S. by the State Department. The law doesn’t exactly give the executive the ability to arbitrarily decide where to relocate these refugees, but it does instruct the director of the Office of Refugee Resettlement (which is part of Health and Human Services) to develop a strategy for resettling refugees in the U.S. in a way that will “insure the refugee is not initially placed or resettled in an area highly impacted… by the presence of refugees.”

The law requires the ORR director to take several criteria into account, including how many refugees are resettled in a given area, what kinds of resources are available to refugees in terms of employment, housing, and other needs, and how likely the resettlement is to prompt more refugees arriving or moving away (8 USC 1522(a)(2)(C)). The statute also lays out that “[w]ith respect to the location of placement of refugees within a State... [the director] shall… to the maximum extent possible, take into account recommendations of the State” ((a)(2)(D)).

The administration is leaning on in this last section in its order, essentially claiming that handing states and localities veto power over refugee resettlement is the logical “maximum extent possible” of consultation. The order gives the Secretaries of State and HHS 90 days to develop a process for states and localities that are candidates to receive refugees to provide written confirmation that they agree to resettlement. It’s not opt-out, but an opt-in structure; areas that want refugees will have to indicate so affirmatively. States can present their own longer-term refugee resettlement plans and receive program funds from HHS. However, up until now, a state’s refusal to actively participate did not stop refugees from being resettled there. (There’s an exception for the spouses and children of refugees already settled in the U.S.)

The VOLAGs, which run the initial, 30- to 90-day initiatives to find homes for refugees and help them acclimate, build skills, and find employment, provide the government with detailed proposals and in turn receive grant funding and typically get a significant say in where refugees are placed. Under this order, they would be unable to get the State Department to resettle refugees in their designated areas without a locality and state signing off. This would only constrain refugees for the purposes of initial settlement; once they were in the country, they would be free to move wherever they pleased, just like anyone else. That said, they wouldn’t have access to the same level of services in areas where the government wasn’t funding resettlement programs.

On November 21st, three of the nine VOLAGs — HIAS, Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service, and Church World Service — sued the administration in the federal court for the Southern District of Maryland, alleging that the administration was already requiring these written consents to be included in resettlement proposals for the next fiscal year, and requesting an injunction against the new policy.

How we got here

The Refugee Act of 1980 systematized the way the U.S. handled refugee admissions, as well as the way refugees were resettled and integrated into the U.S. Both “refugee” and “asylum seeker” are post-World War II forms of classification — but unlike political asylum, which at the time was primarily intended for people fleeing Eastern Bloc countries, refugee status primarily applies to people who have been displaced from their homes because of war, conflict, or another reason.

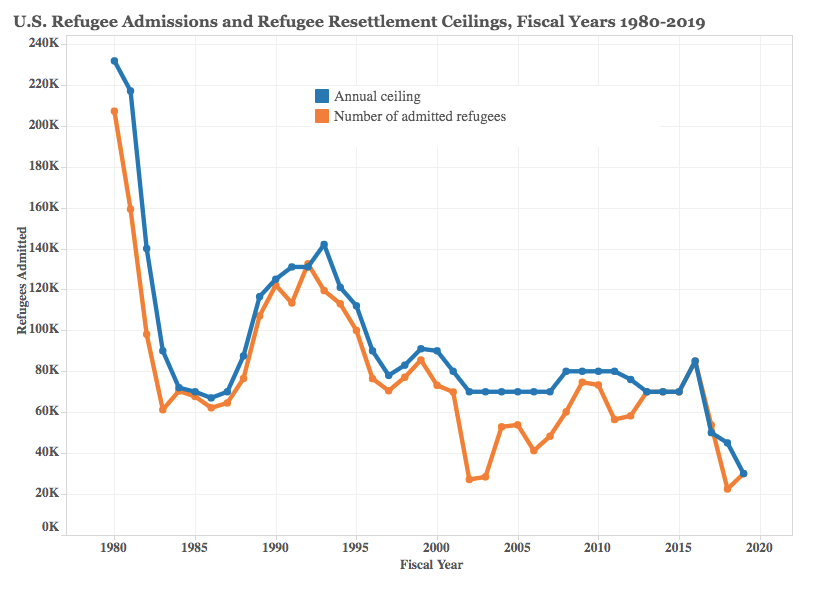

As the below graph shows, the Trump administration’s most recent refugee cap of 18,000 is an all-time low, but the overall ceiling on refugee admissions has never been as high as it was after the law was first passed. Refugee admissions hit the then-historic low in the wake of the 9/11 attacks amid concerns about national security: even though the cap was 70,000 in fiscal 2002, just 27,131 refugees were let into the U.S.

(Source: Migration Policy Institute)

Unlike asylum seekers, who primarily come from Latin America and the Caribbean, refugees typically hail from Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. (When the program was first introduced, many refugees came from the Soviet Union, according to Pew) The high rate of refugees from these countries makes sense, particularly given the U.S.’s extensive involvement in the Middle East — to put it lightly — over the last few decades. But since 9/11 in particular, a subset of Americans have assumed any Arab or Muslim refugee could be a threat to national security, even though refugees have to undergo a series of intense background checks before being approved for resettlement in the U.S. (It’s worth noting that the overwhelming majority of displaced people deemed refugees by the UNHCR will never be resettled in the U.S.; many will not be resettled in any safe third country.)

Local leaders have voiced opposition to refugees being resettled in their states in the past. In 2015, 30 Republican governors, joined by one lone Democrat, said they didn’t want the federal government to send Syrian refugees to their state. At the time, the U.S. had only admitted 1,500 Syrian refugees over four years. Ultimately, though, the executive branch decides how many refugees are resettled each year, and where those refugees go — and with this recent executive order, the Trump administration seems to be counting on a wave of anti-refugee resentment to make the resettlement process even more difficult than it already is.

Trump has tried to all but end refugee admissions in the past. His January 2017 executive order banning travel from a number of Muslim-majority countries — titled Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States — initially included a provision that the refugee admissions program for 120 days and suspended Syrian refugee admission indefinitely. (The initial version of the order was revoked after a federal court issued an injunction; Trump issued a subsequent order in March.) The order also stipulated that “State and local jurisdictions be granted a role in the process of determining the placement or settlement” of refugees there, and required the Secretary of State to determine how to give state and local jurisdictions “greater involvement” in the resettlement process.

The executive order, commonly referred to as the Muslim ban, also prioritized the admission of minority religious groups fleeing religious persecution in their countries, which in practice almost exclusively meant Christians. Though these provisions were removed from later versions of the travel ban after a legal battle, the intent was clear. And as Pew notes, the U.S. has begun admitting more Christian refugees than Muslim refugees under Trump: In fiscal 2019, 79% of the refugees who came to the U.S. were Christians.

What’s next?

From a legal standpoint, the resettlement agencies are arguing the law requires that state-level recommendations be taken into account with regards “the location of placement of refugees within a State” (emphasis theirs), and this is not meant to give the state as a whole the ability to contest resettlements. They’re also claiming Congress never intended the mandatory consultation with states and localities to mean local officials could veto resettlement decisions. “Consultation” within the refugee context itself is often a formality. For example, the president is mandated to consult with Congress in setting refugee caps, but is by no means required to adopt its recommendations.

The lawsuit, like many others, brings up Trump’s history of disparaging comments about the refugee program and his various efforts to interfere with it, including the January 2017 travel ban. Some refugees who were all set to travel to the U.S. in that timeframe had key documents expire as they waited, and have still not made it now, nearly three years later.

In terms of practicality, the suit raises several points. It notes that the term “locality” is never defined in the order, and thus leaves it unclear which state sub-division, exactly, must be consulted. It also alleges that the most recent funding notice issued by the State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM) already specifies that written consents must be included in agencies’ proposals to resettle for the 2020 fiscal year, and directs agencies themselves to obtain it from each locality they are proposing, a cumbersome process. It also claims the requirements don’t seem to account for carve-outs, such as families following a resettled refugee.

It seems likely that the policy will be enjoined. There are a lot of contexts in federal law in which some party or another is to be consulted on a decision; very rarely is it understood that the consulted entity gets a final say over the decision. Further, if the statute demands that refugees be placed in the areas where they’re most likely to succeed and become self-sufficient, allowing local government officials to block resettlement in places that are otherwise well-equipped to receive them would appear to run counter to the law.

If an injunction is not issued, then the agencies will be forced to go along as the case is litigated. This will probably result in halting resettlements to states that have previously fought against it, like Alabama and Indiana. Some refugees who are resettled elsewhere will probably still make their way to what would have been their original destinations, especially if there are pre-established refugee communities or they have family members there.

Under the Radar

ICE increases its focus on workplace investigations under Trump

Investigators with ICE’s Homeland Security Investigations unit opened 6,812 new workplace cases in fiscal 2019, the Wall Street Journal reports. For context, ICE conducted 1,701 workplace investigations in fiscal 2016, meaning workplace investigations have roughly quadrupled over the past three fiscal years. Workplace raids, a hallmark of the Bush era, have experienced a renaissance under Trump. It’s easy to see why the administration is investing in workplace stings. For one, massive workplace raids like the one in Mississippi that resulted in the arrest of 680 undocumented workers, are a massive spectacle. Shock and awe aside, these raids also give ICE access to immigrants it may not have had on its radar but can arrest for immigration violations anyway — these are referred to as “collateral arrests.” (The companies targeted by these raids by the way, are rarely charged with any crime.)

But according to the journal, the heightened focus on workplace investigations — which typically take months or years to carry out before leading to a raid — have come at a cost. Investigations of weapons smuggling, for example, dropped by 43% between FY16 and FY19.

ICE bought a year’s worth of access to North Carolina driver’s license data for less than $27

According to Quartz, ICE’s Enforcement and Removal Operations division paid North Carolina $26.50 for access to its DMV records from June 2017 to June 2018. Notably, North Carolina doesn’t let undocumented immigrants get driver’s licenses, but an internal ICE memo obtained by the National Immigration Law Center and reviewed by Quartz explains how ICE could use this to its advantage. Basically, license renewal applications denied because the applicant lacks proof of residency “provide a significant foreign-born target base which could be vetted further to identify those with prior criminal convictions,” the memo reads.

Like other federal law enforcement agencies, ICE relies on a network of databases to track down and arrest immigrants in the U.S. In October, the New York Times magazine published an enlightening investigation into how ERO uses public and private databases — like DMV records and the Thomson Reuters service CLEAR — as well as social media to zero in on its targets.

Next Destination

U.S. considers terrorism designation for Mexican cartels

Since it came to light that the administration was weighing the prospect of officially designating Mexican narco-trafficking organizations as international terrorism organizations, much of the discourse has been around what this would mean for security cooperation between the U.S. and Mexico. However, such a move could also have big implications for immigration. One of the various factors that can make a person officially “inadmissible” to the U.S. — unable to obtain legal status of any type — is having provided “material support” to a terrorist organization. This provision is ostensibly intended to prevent people who have worked with or provided financial support to a terrorist organization from entering the country.

However, the Board of Immigration Appeals has ruled that there is no general duress exemption to this law, leading to situations like a Salvadoran woman forced to do housework for a guerilla under threat of death being declared inadmissible on terrorism support grounds. Waivers are available but difficult to obtain, and the administration is interested in getting rid of them entirely. If cartels are designated terrorist organizations, we’ll likely see Mexicans being denied all types of statuses, from asylum to permanent residency, on the grounds of having provided support to a terrorist organization for offenses like paying a ransom for a kidnapped family member or paying extortion money to cartels under threat of death.

Ninth Circuit appears skeptical of asylum ban — CNN

A three-judge panel of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals seemed skeptical of the Trump administration’s argument that migrants crossing through Guatemala or Mexico could safely apply for asylum in those countries prior to arriving in the United States. Though a district court had initially issued an injunction preventing the asylum ban policy from being implemented, the Supreme Court cleared the way for it to remain in place as litigation continues.

The judges all questioned government lawyers as to whether it was safe for migrants to receive asylum in those countries, indicating a willingness to take foreign country conditions into account in issuing a ruling. A decision in this case would only affect the asylum ban, and not the safe third country agreements signed with Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, but the same arguments about the safety of local conditions could come into play in legal challenges to those agreements.